|

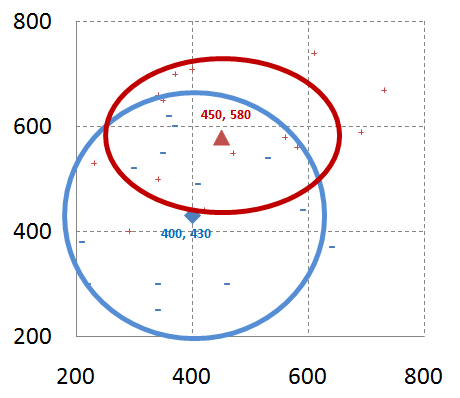

Fast readers read and think with their intuitions. What is your language intuition, English in particular? This graph explains it well. sSitting on top is the meaning of the text that is to be read off. To get it is to understand it (the left arch on the graph). For you to understand something, you'll have to process the text information input into your conscious. This process requires a set of neurological functions performed in your cortices. These are the biochemical processes that happen in and between the neurons facilitated by a number of substances among which are neurotransmitters such as dopamine, GABA, and endorphin.

You need a basic level of such substances to understand the easy texts whose structure is simple and meaning explicit, but it will take you a lot more if text structure becomes complex and meaning in-explicit. The question is not how much neurotransmitters you should prepare for yourself — you can by no means manage the exact amount. The question is how you prepare (or produce) more when you need them? Your hypothalamus knows how to and produces them for you, and you just need to tell the hypo to bring it up at times especially when facing hard, in-explicit text. This message is constructed in the form of an complex emotion that is typically a product of your subjective feeling of your own success rate in understanding that text. When you feel positive of your efforts, a complacency emotion tells your hypo to bring up the neurotransmitters. The more the neurotransmitters, the faster you are to understand the text. On the contrary, any negative feeling of yourself tells the hypo not to produce more neurotransmitters. Moving on, as the transmitters are consumed, you have diminishing chances to understand the text. This complacent emotion, is your language intuition (the element sitting on bottom of the graph). It is generally built through years of reading experience, ideally on a variety of subjects and genres. That is the case for a natural good reader. However, you are not doomed if you are not already one of them. Intuition can also be built through systematic but quick training. This generally consists a number of ways to reproduce texts (right arch on the graph) from good sources. One of most effective technique I use is to read loud and fast, some times to recite the entire passage by memory. Being able to reproduce the text drives the intuition, thus creates a complacency before even understanding the text. In reality of reading, text reproduction indeed happens unnoticeably in your cortices and signals the hypo for more neurotransmitters. Thus, reproduction, intuition, understanding, and meaning forms a full cycle of neurological process of reading. The key in building or breaking this cycle, a factor that can be proactively controlled by yourself, lies in the ability to reproduce the text.

0 Comments

Subconscious Learning

Unified Models of mind2learn Subconscious is not a de novo subject. Sigmund Freud first described it as the part of human mind that is not in focal awareness. Although Freud switched to “unconscious” not long after, others kept referring to it as one of most important psychological terms. For the purpose of this blog, I still prefer to use subconscious, since it seems there must be a divide within the so called “unconscious” mind. One part is hardly accessible once it is developed, and the other is linked to the conscious mind and teachable if a proper pedagogy is applied. Subconscious demonstrates many properties that conscious doesn’t. Most striking feature of it lies in the neurological capacity. Scientists estimate that subconscious makes about 70-95% of the neurological mind (averaging 90%), and conscious is only 10%. The famous notion that Einstein uses 12% of his brain while everyone else 10% is probably true because Einstein was able to access his subconscious. Subconscious not only takes a larger capacity in our brain, it is also loaded with a multi-core system. It can simultaneously run more than one neurological processing and direct different body parts to work. For example, we eat and talk when we have dinner with a friend. While our conscious is on the talk and fun, our hands in picking food up and mouth in biting food can both take place without the focal awareness. Subconscious are also chaos-based, ideologically unbiased, emotionally activated, flexibly inputted, etc. All these features lead to a much desirable one for the sake of timed tasks such as SAT—subconscious is much faster and unambiguous than conscious. Think of the choices you experienced in the SAT. An easy one took you an instant to figure out the truthfulness so that you don’t seem have given it noticeable thought process. The hard ones, you might have spent a minute or two to come to conclusion. While the latter is a conscious one, the former may be a subconscious driven process that other prep guides tend to note as obvious. What if you can make the hard one as obvious as the easy one? This is what all the prep guides have been trying to do in past 70 years and failed in most of us. Their coaching process works only in your conscious. So you are trained to analysis the questions, but with a much slower speed than SAT requires. Unified Models of mind2learn does it differently for you. We take you through a thinking model that only requires and trains you innate logical capabilities (to compare and to contrast) so that you can touch down your own subconscious. Eventually, you will be able to think more efficiently and accurately on the reading, writing and math questions. When the right choices should look to you much friendly and wrong ones much hostile, how can you not make that score point? It is time to update the annual SAT:PSAT conversion for 2018. All students took PSAT/NMSQT in the fall of 2018 should have received their test report from College Board. Taking this test as a warm up, you must have been trying to understand what is your chance for the school day SAT test that happen in the mid of next spring. Much of your performance on that day will determine your college desires. According to data published by College Board’s 2018 annual SAT Suite Assessment Report, I have computed the 2018 conversion from PSAT to SAT. Hope this will help you get a fair expectation for next spring. SAT = PSAT + [80 : 120 : 80 / 1400 : 1000] How to work on this conversion formula?

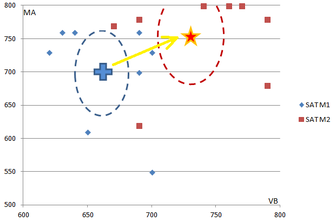

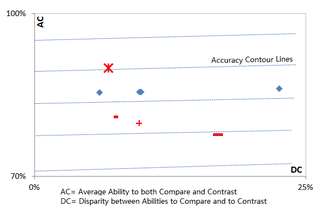

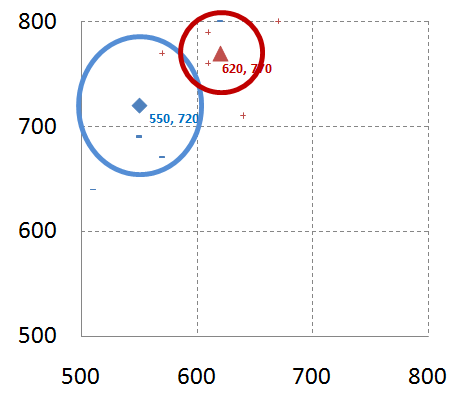

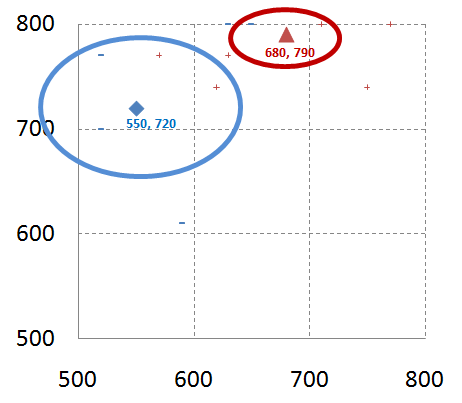

Please note a few things about the formula. First, the formula is made to be simple and approximate. So, don’t take it as an exact estimate. Second, it doesn’t consider the practice and training that you may take between your PSAT and SAT. I encourage every one to plan for practice on SAT heading to the spring. Last, the formula assumes that you can at least maintain your test proficiency between PSAT and SAT tests. So, if you just sit and relax before the next spring, you still have a fair chance to lose some score points. As we just completed a 5-day camp in Chicago, it makes sense to summarize what I observed among these eight students from south and west of Chicago suburban schools. Let me start with the chart. Overall, the students reached a growth of 150 score points on their SAT levels, of which 100 counts towards verbal and 50 on math. These gains rank similar to the gains among the students in the weekly camps earlier this year, around Chinese New Year. While almost every one realized stunning gains, two students attracted much of my attention, Caro and Ale. They both belong to the high level subgroup of four who had already made themselves 690-700 in verbal. A mid level subgroup consists of another four students with 620-660 in verbal. Caro and Ale did not move up in verbal as their peers during the five days. What caused it? To find it out, we have to graph a different chart. The dominant factor describes the your average ability to think both comparatively and contrastively. Compare and contrast as two and only fundamental elements of critical thinking. Not only that your neurons are designed to perform these two jobs, these abilities on complicated objects are built as you are trained throughout the years. Most of times you just need this average factor to tell how well we can do in school subjects. Same is true in any tests.

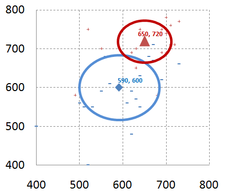

Taking it to the standard test, there is a second factor that contributes to your overall accuracy. It is the difference between your two abilities. The bigger the disparity, the lower the overall accuracy. When you are better in comparing than in contrasting (or the other way around), your overall accuracy is driven down. Taking two factors into account, you generally want high and balanced levels of comparative and contrastive thinking. Looking at Caro and Ale, I found exactly the same pattern of their comparing v.s. contrasting abilities. Both maintain excellent levels of either compare or contrast, while both have the other ability as non-desirable. As a result, their overall accuracy is dragged. Comparing and contrasting are drivers to your learning curve. When you learn new things, the first ability you call on is comparing. Being able to tell similarity between the new information and existing ones means understanding. When you fully comprehend, the next thing you do is experimenting with it. This takes more or less the braveness or risk-averse in reality. Nothing can be learnt but never tried. To try is to familiarize you with the differences that come with it. In this step, you start with contrast, and ends with comparison that embraces the newly experienced differences. It is by both comparing and contrasting that we eventually learn anything. If you are one who shines at your school but is stranded by standard tests, you are likely having the same problem as Caro and Ale. Abilities to compare and contrast often go against each other when either one is overwhelmingly trained or used. Nowadays in school, the ability to compare is often the one you are mostly good at. Being able to contrast effectively is likely what you need leading to your next test. It is a good time to let our first annual stats heard. In 2017, probably the first full-calendar-year cycle of mind2learn’s official operation, we hosted 4 SAT camps in Chicago and Shanghai and worked with about 50 students, from both American and Chinese high schools, for a total of 270 hours of lectures and guided practice. On the annual average, our students have been rewarded 85-point and 105-point of gains in English and Math, respectively, for their hard work. 28 students gained more than 50 in their English subsection score, while 29 students gained more than 50 in Math. Altogether, 34 students added more than 100 in their total SAT. The programs here raised 11 students to 700+ in English and 26 students to 700+ in math. Stunning individual performances, such as one from 650 to 770 in English or another from 600 to 760 in Math, have been disclosed in separate notices.

思维之道:求同和求异

In a time of two and half millenniums ago, Lao Tsu, an ancient philosopher in China, studied a breadth of subjects in the then-biggest collection of human experience recorded on bamboo slips. He processed all those information in a couple dozens of years and summed up his learning of all in one simple sentence — “Tao begot one, one begot two, two begot three, three begot all.” This is by far the most effective and efficient learning process on big data, and it was completed once through no computer but with Lao Tsu’s own manpower — his Tao of minds. How could he do it? The secret is simple — by comparing and contrasting information. Comparing leads to similarity, while contrasting leads to disparity. It is through similarity that we confirm existing knowledge, and disparity that we discover new. Both are innate capacities of our brain, down to the neuron cells and the synapses that these cells are made to perform. All human knowledge is produced through either or both of these two basic biological intellectual capacities. It is very unfortunate that today's school learning, or knowledge learning in general, interferes with our inborn intellects, the comparing and contrasting. Knowledge, meant to save the successors from the mental suffer experienced the predecessors, has demonstrated a subprime effect of muting the successors’ inborn capacity. When you take in 1+1=2, for example, you have not bothered to think much in its necessary and real term that this abstract mathematical principle is made non-provable. How to make students learn while conserve their innate intellects is not a simple question to answer here. But you need to know that top achievers in schools are simultaneously good in learning knowledge and conserving their innate intellects — the Tao of minds. I have included a few sample questions for you to test and exercise your mental power. If you can tell the similarities and disparities of the choices of the following questions through your own Tao of minds, your chances to fly in the SAT test will be much high — better than you may think of. Pick one choice that is clearly different from the other three in each question. 1. The main purpose of the passage is to: A) analyze a series of historic events B) persuade readers to support an unusual practice C) alert readers to an urgent societal problem D) describe the underlying causes of a political change 2. What the word “best” most likely means? A) superior B) excellent C) genuine D) rarest 3. The main purpose of the passage is to: A) emphasize the value of a tradition B) stress the urgency of an issue C) highlight the severity of social divisions D) question the feasibility of an undertaking 4. What the word “hold” most nearly means? A) maintain B) grip C) restraint D) withstand 5. What the word “demand” most likely means? A) offer B) claim C) inquire D) desire 6. What does the author suggest of men’s primary motive towards women? A) A selfish desire to deprive women of even smallest joy B) A pragmatic impulse to maximize contentment C) A cruel tendency to afford then withhold affections D) A well meaning but ultimately ineffectual intent to act fairly For explanations, you may contact us through email: [email protected], with a title line of "Tao of Minds." There is long a recorded gender divide among American high school students in terms of SAT test scores. According to a study by ETS, girls have consistently under-performed boys in both SAT math and reading during 1967-2004. The gender gap was 30 score points for both subjects before the mid 90s. An encouraging trend came at that time when changes started to take place in American K-12 education. As a result, the average SAT scores increased across the subjects and genders by 20 points except for boys’ reading that only changed minimally. As a result, the gender gap in reading shrank but that in math persisted.

The cross-board increases came from recentering in 1995 SAT test scores, a measure that arbitrarily moved the average back to around 500. In the 30 years prior to 1995, these averages had degraded to 425 in verbal and 475 in math. As an effect of the change, a 500 in verbal prior to 1995 corresponds to 580 in 1995, and 500 in math prior to 1995 means 520 in 1995. A handful researches have studied the issue but reached no conclusion. AEI, a leading think tank in Washington, DC, attributes the gap to the student quality in general. “One possible explanation…would be that high school boys are better students on average than high school girls and are better prepared in mathematics than their female classmates.” Another popular view takes the issue to stereotype bias, a psychological phenomenon whose scientific cause is yet unknown. Both explanations failed to account the trends in American high school classrooms. The afore-mentioned ETS research found that girls had spent increasingly more hours and studied in more courses in math subjects in school since 1990s. On the contrary, boys’ effort in math has been stagnant if not declining. As a result, arguably, girls outperform boys in terms of math grades. In spite of girls’ growing outperformance in class, the divide has persisted over the period. What, then, is the real cause? The answer, as I recently found, lies in a gender bias in the SAT test design. In my summer SAT prep camp in Naperville, I came into this fantastic idea to motivate students to practice CRM model. Standard SAT requires students to choose one and eliminate three out of four choices for each question. Instead, I allowed the students to choose two and eliminate two, and record their results as R(2). Then, they are allowed to make their final choice and the result is recorded as R(1). I collected both results and graded them separately in that a result scores 1 if it contains the final correct answer. Typically, to distinct between the last two choices is the harder than among all four. While the adaptation helped many students in learning the CRM model, I noticed a surprising and consistent pattern among the students. Girls score consistently higher than the boys in R(2), but fall behind in R(1). I concluded that even though girls are better in choosing two, their ability to eliminate the last one is a fraction of that of the boys. The girls revealed to me that they tend to stuck in the similarity of the last two. The boys, on the other hand, do not have much difficulty in telling difference of the two in R(1). In fact, they see differences of all four and eliminate two in R(2). The cause of it, as I further analyzed, is the gender difference in terms of critical thinking, including both comparing and contrasting among things. Girls are better comparing things, while boys are better contrasting. In R(2) stage, students started with all four choices. Girls compared them with the reading materials find two most obviously similar ones as their choices. Boys, on the other hand, saw one or two choices are obviously irrelevant to the reading topic as they understood. As girls generally read more careful then boys, they excelled in R(2). In the next R(1) stage, girls seemingly proficient with similarity could not tell as much the difference between the last two as did the boys who are obsessed with contrasting. All SAT tests are designed in the same way that you have to pick one exact rightness out of three distinct wrongsome. When many of the wrongs are made very confusing, the ability to contrast helps much more than that to compare does. Girls who are made by our nature mother to see the commonalities more easily than the difference are thus discriminated by such a test design. Mind2learn has since turned out its training mechanisms to cope with the situation, but I still hope that SAT may eventually find their way to correct such a deficiency. So, your August SATs have been reported. Ours too. Students who learnt mind2learn’s unified model in the 6 flying days in end of July have realized 120+ gains in their reports. These include one of my favorite students, the humorous Andy, who was stuck in 1100s since this spring but made an elegant 1370 in August. On the other side, a few boys and girls followed me for a 3-week camp and took 160+ gains. The biggest individual leap comes from a senior girl from Xi’An— she made it from 1050 to 1320. Another stunning performance is made by a 1450-May senior by shooting an extraordinary 1570. Almost every one made 100+ gains except two quiet girls. One merely added 10, another 60. They are the ones who are taking all of my breath from now on. The model still have to be revised for students of them alike in order to strike 100+, and eventually claim 700s, in English. My goal is still that everyone who take the pain to learn my models must reach 700+ in 30 hours of learning. Unabridged! + + + Cheers or chills you have wouldn’t take you far. The meaningful recap of experience would count into real learning. Here are ours too.

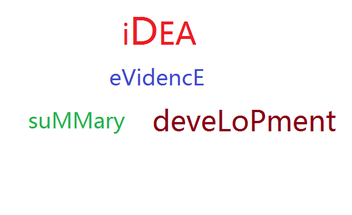

Before continuing the discussion, let’s clear front on the terminology we use here. “Idea”, as used here, means the key idea of a passage. A passage may start with one idea insufficient or conflicting with its key idea, such an idea is also dubbed as “idea” here even though it is not the key idea. “Evidence,” on the other hand, includes a lot of things: proof, description and narration. Proofs can be factual evidence to an idea, or a reasoning point. These “evidences” are used to support the ideas and sometimes ideas by themselves too. Most of the EOI questions ask students the following tasks in the “evidence” level in the IES/D structure. In another word, SAT cares a lot about your capacity to express the idea, when there is one, fluently.

While the third task belongs to the domain of grammar, the first and second tasks are the two categories that SAT started to wage heavily as means to test your EOI. It is estimated that 9 of every ten American high school juniors are not able to perform both tasks successfully. This is probably due to a chronicle deficit accumulated throughout K-12 stages, a problem whose diagnosis is far beyond a couple of blog articles. Instead, let’s focus on a structural fix in your writing. Whether any information belongs to a paragraph depends on its logical relevancy to the evidence, or idea, and rest information in the paragraph. Relevancy can be best defined by referring to the IES/D structure but not otherwise loose terms. Referring to the previous article, IES/D structure takes a few, or three, popular variations. Paragraphs in these variations can be as simple as “I” or “E,” or composite “IE” or “IEI.”

In any of these cases above, you may try to read the context without the information in question. If the absence causes insufficiency and/or incompletion, the information shall be brought back. Incompletion happens where the discussion seems broken in its line of logic. For example, it often sounds awkward that an “IEI” paragraph without an “E” detail that could lead to the introduction of a second idea. Take the following sample for incompletion from an SAT official practice: Over the past generation, people in many parts of the United States have become accustomed to dividing their household waste products into different categories for recycling. For example, paper may go in one container, glass and aluminum in another, regular garbage in a third. (a) Recently, some US cities have added a new category: compost, organic matter such as food scraps and yard debris. (b) Like paper or glass recycling, composting demands a certain amount of effort from the public in order to be successful. But the inconveniences of composting are far outweighed by its benefits. The paragraph is an “IEI.” It first sets up the idea of household waste categorization, then provides exemplary details such as paper, glass and, further, compost. After mentioning the efforts of all waste categorization, it introduces the second idea that composting is still a better-than-not endeavor. It also foreshadows the discussion in the following paragraphs. Try taking either (a) or (b) away, and feel how the whole paragraph would seem broken. These above are paragraphs that with an “I,” what if a paragraph is only concerned with “E.” There is no fundamental difference between simple “I” and “E” paragraphs. While being used as an evidence to support the idea of the passage, information in the “E” paragraph independently falls in same principles as for the “I” paragraphs. In fact, we can treat such “E” as an idea of its own. From the same compost practice article, the following sample can tell us what sufficiency looks like. Most people think of banana peels, egg shells, and dead leaves as “waste,” but compost is actually a valuable resource with multiple practical uses. (A) When utilized as a garden fertilizer, compost provides nutrients to soil and improves plant growth while deterring or killing pests and preventing some plant diseases. (B) It also enhances soil texture, encouraging healthy roots and minimizing or eliminating the need for chemical fertilizers. (C) Better than soil at holding moisture, compost minimizes water waste and storm runoff, increases savings on watering costs, and helps reduce erosion on embankments near bodies of water. (D) In large quantities (which one would expect to see when it is collected for an entire municipality), compost can be converted into a natural gas that can be used as fuel for transportation or heating and cooling systems. The paragraph begins with its “E” that is also an idea itself—compost are valuable and useful. It follows with four details of its usefulness as (A) organic fertilizer, (B) soil enhancer, (C) moisture holder, and (D) source of natural gas. Looking at these details, we find that A, B and C are all ways how compost makes plants healthy while D is another kind of use. Therefore, D is indispensible in this paragraph and have to be placed after ABC. On the other hand, A, B and C talk about how compost making plants healthy by fertilizing, moistening, texturing and keeping way pests and diseases, but in an overlapping way. In case you are asked to delete one, B is the one least needed because it was overlapped by A. At the current required level of SAT, none of A, B and C needs to be deleted because each of them contains information logically relevant to the usefulness of compost. The problem here is the structure of the expression among ABC does not following a mutually exclusive pattern. That’s the cause for its overlapping tone. If none of ABC can be removed, at least they are to be revised. One way of revising it can be the following, thus expression becomes more concise while maintaining its sufficiency. Compost can be used as a garden fertilizer, providing organic nutrients and holding soil moisture for the plants. In addition, at its presence in the soil, compost also helps to kill pest, fend ways diseases and reducing erosion on embankments from nearby bodies of water. + + + Take Away + + + 1. Determine the passage’s and paragraph’s IES/D structure.

2. Determine which way the information functions, either sufficiency or completion. 3. Determine your options in the question that fits best the above conclusion. Since SAT employed only passages in its section 2 (grammar) in 2016, there isn’t a divide on how students may approach the section that contains 44 questions and merely 43 second per question. All in the test prep profession believe that you should read in detail only when necessary. Such a necessity, as they suggest, arises at the presence of EOI questions, where EOI stands for expression of ideas. We know that EOI questions come in three ways, relevancy of information to topic, identity either as idea or evidence, and location or order of information in question. When you are asked on this type of questions, you read in detail to identify the topic (key idea) of the paragraph, determine whether the information is summative or supportive to, or simply off-topic. Then, of cause, to find the right order in which the in-topic information should be placed, displaced or replaced. This framework seems so obvious that many of us, including myself, have been advising it to students. Not until now! Looking at students’ practice, we see that some of the EOI errors are surprisingly consistent throughout the practices. One of the errors is on the determination of relevancy on a particular information. Take a look of the following example: From New Orleans, Armstrong moved to Chicago to join Joe Oliver and his King Oliver Creole Jazz Band. His new big move was to New York, Where the “Harlem Renaissance” was in full swing. Here Armstrong met and collaborated with artists of all types—painters, poets, writers, actors and musicians — and ___________ : Choose one that indicates specific effect of Armstrong’s New York experience on his work: -A. embraced an artistic culture even richer than that in New Orleans; -B. many of whom have become legendary artists in their own right; -C. so his performance become more theatrical and comedic; -D. later would recall this period as one of the most influential in his career. Although the key to the solution lies in the question itsself or a “specific effect …on his work” as stated by the question, many students missed this question more than twice and even after they were explained the correct answers. The cause to the error’s consistency is that all four choices read fine by view of grammar logic when you are not equipped with an eye on the overall EOI structure. If the question is revised into “which choice best fit the discussion here”, you may see very few students survive. However, if you know the article’s EOI structure, this would not be your problem. The article describes the career growth of American Jazz musician Louis Armstrong, following an IE-E-S structure with merely three paragraphs. “I” stands for idea, or key idea that we just stated above. “E” stands for evidences that are generally the supporting information that discusses, describes, explains, proves or narrates the key idea. In the Armstrong article, evidences are his career life lines with an emphasis on his acquisitions and choices in musical values. After Armstrong’s musical start in New Orleans is introduced, his musical specifics along his Chicago-New York-Chicago route is discussed in detail. Thus, having a message on the “more theatrical and comedic” performance of his would be much relevant, if not perfect. Even though A and D both read very well and seem to be related to Armstrong's music career, C is specifically in topic within the paragraph. You can also confirm this if you find Armstrong’s “rhythmic but nonsensical syllables” later in the paragraph. There are two general structures in section 2 passages, IES and IED, both in line with what we discussed in Idea Progressions (click here is you haven’t read this topic). IES is idea-evidence-summary, and IED is idea-evidence-development. The difference between summary and development is whether the passage closes the discussion or indicates an unresolved direction by the end. Considering passages are often (almost) in 4 to 5 paragraphs, variations of both structure are in place. The following three count nearly all of your SAT examples since 2016.

One most common variation is I-E-I-E-S/D. In this structure, passage throws out an initial idea in the first paragraph, then places some evidences in the second. (Sometimes, the first and second may be combined in one so that structure can be IE-I-E-S/D.) In the next paragraph, a new, often competing idea is introduced and then evidence supplied. Last paragraph serves as closing statement or further extension for the entire passage. As you may have noticed, this also looks a lot like the standard structure in our CRM model. The second variation, even more popular, is IEI-E-E-S/D. When you see a very long beginning paragraph, sometimes takes 1/3 to 1/2 of the entire passage, that's it. In such cases, an idea (often a phenomenon or person) is introduced in the very beginning with some illustrating details. But the first paragraph generally doesn’t stop here, instead it points out a concern or question about the idea or phenomenon. It indicates but may not give out an second idea straightly in the first paragraph. The following 2-3 paragraphs go on with all the evidences, and then a closing paragraph of summary or development. The last common variation is I-E-E-E-S/D. Unlike the first two structures where two ideas are discussed, this third one employs only one key idea but gives out a lot more supporting information. It is very common when the passage’s main objective is to explain basics of a phenomenon or object, or describe a person’s life or career. It may be needless to employ two competing ideas in such occasions. The Armstrong examples falls in this structure. In taking a section 2 test, you shall have these structures in mind before you start to address the questions. When asked for an EOI question, identifying the paragraph in the overall structure first — being it as simple as “I”, “E” or “S/D”, or complicate as “IE” and “IEI” — will help you to make your choices. It not only helps in determining the information relevancy, it can also help to determine the location or order on a good piece of information that you sure must keep. We will talk about this in next blog. |

The F‘LOGsthink, teach and enjoy Archives

November 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed